- Torrent Femme Fatales 2011 2012 Bmw

- Femme Fatales Tv Series

- Torrent Femme Fatales 2011 2012 Roster

- Femme Fatale Movie

Cover of the premiere issue of Femme Fatales, Summer 1992, featuring B-movie actress Brinke Stevens. | |

| Categories | Men's magazines, Film journals and magazines |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Bi-monthly |

| Circulation | 70,000 |

| Publisher | David E. Williams |

| First issue | Summer 1992 |

| Final issue | Fall 2008 |

| Company | Femme Fatales Media |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| ISSN | 1062-3906 |

Vudu - Watch Movies. 1 Complete 720p torrent or any other torrent from the Video HD - TV shows. Femme fatales femme. Femme fatales season 2 femme fatales marvel. Full episodes of TV show Femme Fatales (season 1, 2, 3) in mp4 avi and mkv download free.

Femme Fatales was an Americanmen's magazine focusing on film and television actresses. It was in circulation between 1992 and 2008.

History and profile[edit]

Femme Fatales was founded by Frederick S. Clarke in the summer of 1992, as the sister publication of his science fiction film magazine Cinefantastique. Published by Clarke, it was originally edited by pin-up photography collector and expert Bill George. Cinefantastique contributor Dan Cziraky joined the staff as Associate Editor several months prior to its launch. It focused on science-fiction, fantasy, and horror actresses, from B-movies to Academy Award winners, featuring provocative non-nude photography pictorials, alongside extensive career interviews. It was unique in that it encouraged contributions from the actresses themselves, and featured articles penned by 'scream queens' Brinke Stevens, Tina-Desiree Berg and Debbie Rochon, amongst others. Interviews with filmmakers that helped bolster the 'scream queen' market, such as Andy Sidaris and Fred Olen Ray, were also featured. It was a publishing success, at one time producing an issue every three weeks.[1] Cziraky left the magazine in 1994 over creative differences with George, and was replaced as Associate Editor by Rochon.

Clarke committed suicide in 2000, and for two years, both magazines were published by his widow, Celeste Casey Clarke. At the end of 2002, Femme Fatales was published bi-monthly, and had an unaudited circulation of 70,000. In 2002, Clarke contacted Mark A. Altman, the president and chief operating officer of Mindfire Entertainment, a film/TV writer and producer, the former editor-in-chief of Sci-Fi Universe and a regular contributor to both Cinefantastique and Femme Fatales, allowing Mindfire to take over their publication. David E. Williams, a former executive features editor at The Hollywood Reporter, became editor-in-chief of both publications. Both magazines' operations were moved from Chicago to Culver City.

Williams planned the 2003 revamp of Femme Fatales as a version of the men's magazine Maxim focusing on actresses in science fiction and horror films.

After a brief hiatus, Mark Gottwald took over publication and Femme Fatales began printing again in at the end of 2007 as a bi-monthly magazine. The final issue of Femme Fatales was printed in September 2008 and featured Jolene Blalock on the cover.

Femme Fatales was purchased by Williams in 2010.

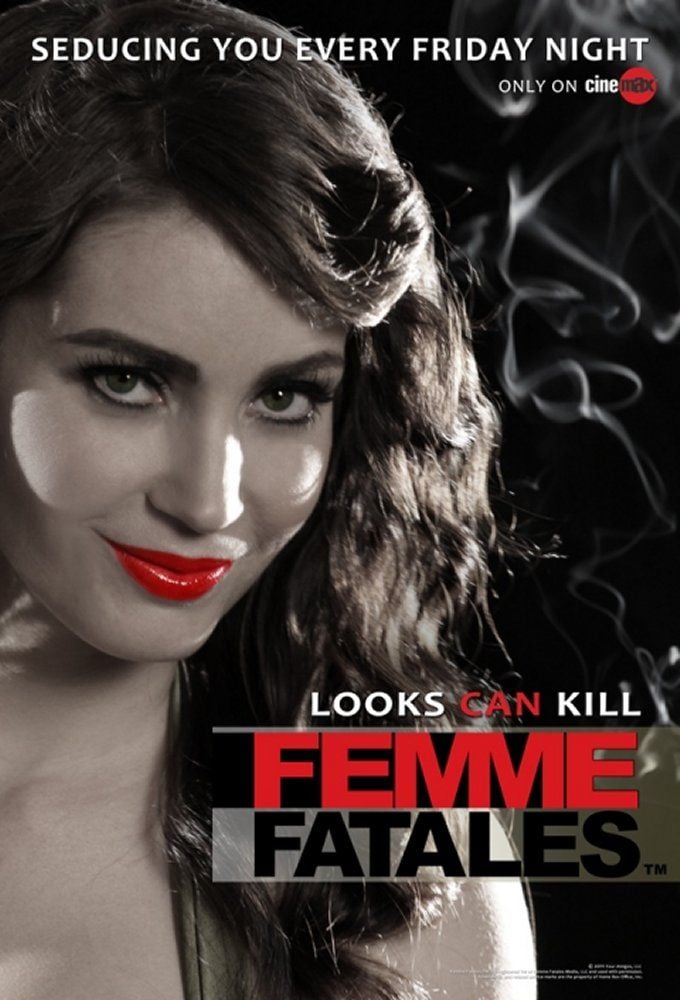

The magazine became the basis of the film noir-inspired HBO/Cinemax series Femme Fatales, 13 episodes of which were originally ordered and began to air on May 13, 2011. On July 15, 2011 it was announced that 13 more episodes of the show were ordered and were to early 2012.[2]

Mark A. Altman is the co-creator and executive producer of the show while Williams is credited as co-executive producer.

References[edit]

- ^Jones, Alan (November 21, 2000). 'Frederick Clarke'. The Guardian. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^Rice, Annette (July 14, 2011). 'Cinemax renews 'Femme Fatales' for second season'. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

For my study of tropes in the media, I’ve chosen to explore the different depictions and symbols of femme fatale in history. A femme fatale is a character that I’ve always associated with sexuality, power and insanity. The first image that appeared in my mind was that of Uma Thurman as Poison Ivy in 1997’s Batman and Robin. My notion of femme fatale stems from how women’s sexuality had been manipulated in the media during the late 90s up until the early 2000s. However—after seeing Aubrey Beardsley’s illustration in one of the lectures—I wanted to have a better understanding of the history of the femme fatale trope. I’m specifically interested in how this trope was depicted during its prevalence in Art Nouveau and in Film Noir. I will be reflecting on Aubrey Beardsley’s illustration of Salomé, Gustav Klimt’s painting of Judith and the Head of Holofernes, and the popularity of femme fatale characters (Kitty Collins for example) in Film Noir. In this exploration, my overall objective is to have a better understanding of whether the femme fatale trope celebrates the power and capabilities of women, if it implies the dangers of female sexuality when it’s unleashed, or indicates a combination of both motives.

The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley

Salomé was a play written by Oscar Wilde, who commissioned Aubrey Beardsley to illustrate it in 1893. To my surprise, Beardsley created these highly erotic and symbolic illustrations at the age of 21. The black and white ink illustrations by Beardsley have compelling line work with decorative motifs characteristic of the Art Nouveau movement. When I first saw the illustrations in the lecture, I had a hard time identifying the female from the male figure. I found that the blurring of gender lines and sexual ambiguity was a deliberate move by Beardsley, which was progressive for that time period. In the illustration, Climax, however, I was able to identify Salomé as the one floating and grasping the head of John the Baptist. This portrayal of Salomé floating ties the femme fatale to some type of supernatural or otherworldly power.

Among the common symbolic elements of the femme fatale, Beardsley illustrates Salomé as a character who literally wields her power over the man with her hair. Salomé’s ensnaring hair reminds me of that of Medusa’s—an image that diverges from what I subconsciously associated as examples of femme fatale—physical characteristics of stereotypical glamor and sexual femininity. Instead, what I see in Beardsley’s illustration are features of a monstrous creature. This scene is symbolic of the changing culture of the time in the evolving role of women. Although there are necrophiliac undertones, I am more drawn to how Beardsley emphasizes the powerful capabilities of Salomé. Even through the suggestions of necrophilia, Beardsley breaks down the boundaries of the Victorian Era’s lauded view of women as pure and vulnerable victims.

I’d never heard of Salomé prior to the lecture and researching her story helped me view Beardsley’s illustration with some more context. According to the Bible, Salomé’s mother Herodias wanted John the Baptist killed because he spoke against her marriage to her brother-in-law, Herod. When Herod was hosting a feast, Salomé, his step daughter, danced for the event. Seduced by her erotic dance, Herod was ready to give Salomé anything she asked for. As motivated by her mother, Salomé asked for the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Through Beardsley’s illustrations, I am able to see past the surface of Salomé’s character as a vengeful vixen. Instead, I see a self-sufficient woman adopting a persona and her mother’s goal as her own. Her desire to kill John the Baptist becomes entirely independent of her mother’s vengeance. Beardsley and Wilde’s collaboration in a way stomps all over the arresting social norms for women of that time. ”Furthermore, it “struck a nerve,” writes Yelena Primorac at Victorian Web, with its ‘portrayal of woman in extreme opposition to the traditional notion of virtuous, pure, clean and asexual womanhood the Victorians felt comfortable living with.’”Beardsley transforms the beauty and power of Salomé into something grotesque and crystallizes misogynist myths and fears about female behaviour.

The next example of femme fatale that I would like to probe is Judith I—an oil painting by Gustav Klimt created in 1901. Prior to knowing the title of this piece, I assumed that it’s a painting of Salomé. After some research, I understood that I wasn’t alone in having mistaken Judith for Salomé in Klimt’s painting. Just by looking at this work, I observed the way in which Klimt has depicted Judith as a femme fatale and a seductive necrophiliac. In Klimt’s painting, Judith is surrounded by gold leaf indicating a specific type of landscape. When I think about gold leaf, I think about Byzantine iconography and the divine. In a way I see the usage of gold here as a way to deify Judith and uphold her as a goddess.

Her expression is provocative and seductive as the femme fatale trope has suggested throughout history. Her eyes are half closed, mouth open, and she’s scantily clothed. In this context, however, the femme fatale’s orgasmic expression is disturbing in that she is taking pleasure in holding a severed head. I initially didn’t see the decapitated head because it takes up a small corner of the painting. The head of Holofernes is also in shadow while Judith’s face is illuminated with the gold landscape. Judith’s gaze is also one that is looking down at the viewer and there is an uncomfortable casualness in how she holds the head of Holofernes—as if it were an afterthought.

Although Klimt escalates the power of Judith in this painting, there is something eerie about how her sexualization is tied to violence and death. This make me question if Klimt is positively using the femme fatale trope—which one could argue doesn’t purely exist. I believe, however, that he could have made this painting of Salomé, but instead he chose to fetishize the story of Judith and Holofernes. I have yet to come to a conclusion as to whether this piece is a way for Klimt to show his appreciation of an unrepressed feminine sexuality. In a lot of cases the femme fatale are never really seen enjoying being sexual. They play the role as a means to fulfill their end goal—Klimt’s Judith I maybe an exception.

After some research, I quickly discovered why this painting was controversial for its time. “Judith was the biblical heroine who used her beauty to charm and decapitate General Holofernes in order to save her home city of Bethulia from destruction by the enemy, the Assyrian army. The story of Judith became an exemplum of the courage of local people against tyrannical ruler & invaders from afar. It also highlights a woman as the heroine whose dogged belief saves her religious community.” By interpreting and emphasizing this dark sexual pleasure of Judith’s murder, Klimt in a way discredits Judith’s tale as a heroine whose main intention was to save her people.

In my last example, I will be exploring some film stills of iconic femme fatale’s from Film Noir. Film Noir is a genre of cinematographic film “marked by a mood of pessimism, fatalism, and menace.” This film style flaunted dark sexual motivations and largely popularized the femme fatale trope in the 1940s and 50s. In the film stills, I noticed the superficial nature of a male character who underestimates the intelligence and motivations of a beautiful woman. These films have misogynistic undercurrents in that the ill-intentioned femme fatale will ultimately be punished for her sexually enticing and vengeful ways. The films imply that women can only get what they want through allurement, deception and seduction, rather than through any sort of merit. I have contradictory feelings about Film Noir because it helped disrupt the gender norms of the time period by allowing women to play villainous roles and to be overtly sexual.

Femme Fatale in Film Noire

In The Killers you can see the seductive posture of the character Kitty Collins accessorized with long elbow-length gloves, form fitting floor-length satin gown, low neckline, and high heels. Unlike the grotesque examples from Art Nouveau, the femme fatale in Film Noir placed much more emphasis on women’s physical characteristics of stereotypical beauty and sensuality to imply danger. The visual depiction of the femme fatale in Film Noir played a significant role. Their appearance stressed dark allure, fashion, self confidence, and subtle sexuality—traits that differentiated them from the average woman. The wardrobe also contributed to the tone and mood of the film.

Although the archetype of the femme fatale seems like a step backward in its objectification of women—Film Noir actually provided them with an opportunity to not only show their power through sexuality but to also reveal their flaws. “The on-screen persona of the femme fatale fueled the 1940’s spirit of escapism; film noir may have emphasized the darker aspects of human nature, but the stories were typically so fantastic and out of the ordinary that they allowed the viewer to be transported out of the utility of daily life during the war.”

The characteristics that are largely associated with femme fatale is a beautiful woman who can use her seductive nature and unapologetic sexuality as a weapon to entice men into compromising and dangerous situations—at times even leading to their deaths. The dictionary definition confirms these characteristics—”an irresistibly attractive woman, esp. one who leads men into danger or disaster; siren.[< French: literally, fatal woman]. ” In many cases these women are not submissive and possess a threatening power over men. This was in a way empowering and refreshing to see in cultures where there were repetitive depictions of the damsel in distress, or the media which lauded motherhood and wifehood as women’s natural role. I feel that today this idea of a stereotypical femme fatale has faded away because we have self-sufficient alpha females like Amy Dunne in Gone Girl or Marvel characters such as Mystique—roles that stray away from this notion that women are innately good or nurturing. All in all, I feel like this study of the femme fatale trope during different movements has been extremely revealing to me. It helped illuminate some of the misconceptions I had with regard to how the trope was merely a form of objectification, but instead I learned that it helped disrupt the social norms of certain time periods.

Citations:

Images:

1) The Climax

Caption: An 1893 illustration by Aubrey Beardsley for Oscar Wildes play, Salome.

Source: http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/beardsley/30.html

2) Judith I

Caption: Judith and the head of Holofernes oil painting by Gustav Klimt created in 1901.

Torrent Femme Fatales 2011 2012 Bmw

Source: http://digital.belvedere.at/highlights/248982/gustav-klimt/objects

3) Femme Fatale in Film Noire

Femme Fatales Tv Series

Caption: Clockwise from left: Rita Hayworth, Ava Gardner, Gene Tierney

Torrent Femme Fatales 2011 2012 Roster

Source: https://hemlinequarterly.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/femmefatale_eveninggowns.jpg

Femme Fatale Movie

Text: